Greetings, fellow children! Reminder: this is not a full review. Instead I take a closer look at a couple of aspects because nothing says ‘Star Wars fan’ like didactically exploring the minutia. As always, SPOILERS from here on out.

This week on Rebels, Secret Cargo, a new hope is formed, thousands of voices called out in fangasm and were suddenly even louder, and review writers once again try to figure out if it must be ‘Mon Mothma’ or if just ‘Mothma’ will suffice.

Driving, Being Driven

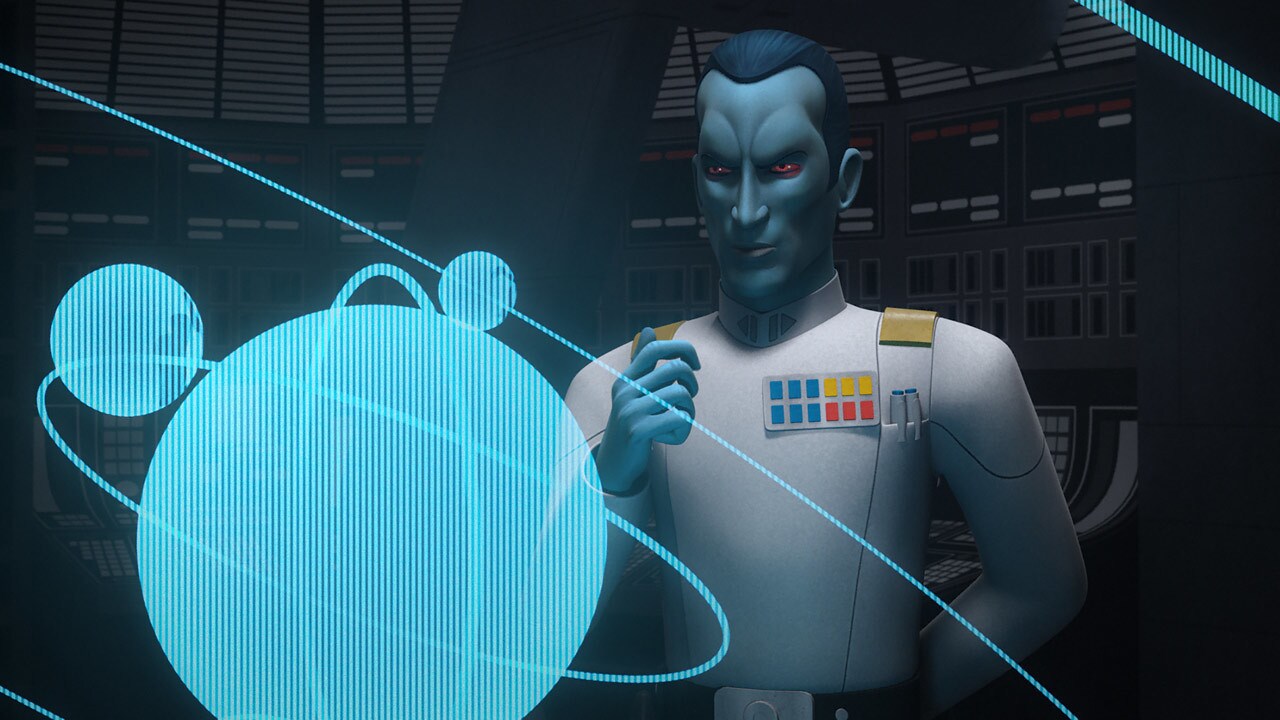

Thrawn is perhaps one of my favourite characters. No surprise there, of course. He’s an incredibly gifted tactician, he fulfils that archetype of the suave, cultured yet very deadly villain with grace and aplomb, and he makes white uniforms look good. I mean, two syllable good. As such I was somewhat worried if the show could even do him justice. It was a silly fear, really, because they are a very gifted team and often do phenomenal work. And indeed they have done Thrawn justice in my eyes – not just because he’s so very cool but because, as epitomised in this episode, he has layers. You know, like an onion. Except without the crying. Okay some crying. I should probably explain.

The specific situation I have in mind is when the Grand Admiral sends Governor Pryce to complete his trap. This is something that Thrawn likes to do – have you noticed? This serves several purposes: one is that his taking a step back enables him to evaluate their performance – but it also gives other Imperials vital experience in tackling the rebels. This is a rather important part of his characterisation. In the books – sorry, I realise it’s a bit iffy to quote chapter and verse, to compare what came before to what is, now. But I promise it’s relevant – in the books, Thrawn took pleasure in turning any possible moment into a teachable moment for his second in command, captain Pellaeon. He did this because he wanted to better his subordinates, to make them more capable officers – and this has thankfully made the trip into this version of Thrawn. It also serves the purpose of giving the other officers a vital morale boost in that, even though they don’t really do anything (sorry, Pryce et al) it makes them feel like they’ve done something worthwhile. Much in the same way that Lord Wellington, in his Peninsular campaign during the Napoleonic War, utilised the Spanish army. Prior to 1809, the Spanish were on allies to France, until France then invaded Spain (and Portugal!), plundering and raping as they went. The Spanish, naturally, were a little miffed at this and so revolted, allying with the UK. The royals fled and the armies, pre Wellington, lost several battles. Morale was low. And then Wellington came along and under his leadership they learned first what minor victories felt like, and then major ones. Even though the Spanish army was ill-trained he deliberately used them because he knew the importance of morale. Under his leadership, their luck – for wont of a better word – turned. They felt good about themselves again. Their pride had been restored – because they were winning.

Now, to return to Star Wars, the Imperials were not wanting for a victory. They could probably point to a planet and bomb it into submission purely for pleasure. But an insurgency is not something they’re particularly trained for and those losses, even though they’re minor, can affect the morale of the Imperial navy. And so Thrawn gives them little jobs to do, things that only an incompetent can mess up, to give them that sense of superiority.

Of course, it serves another purpose in that Thrawn doesn’t take credit for the successes, even though everyone knows they’re his victories. It also means that he doesn’t take the blame for his failures, either, and even though it’s his plan he has the weight of the Imperial Superiority Complex* behind him that ensures his authority is not questioned, but rather that the blame is shifted downwards. There is a phrase in the military to describe this, but this is a PG site and I won’t go there. Anyhoo: As such, his reputation as a winner is maintained while the fault is laid instead at the foot of the simpleton underling he sent to finish the job (again, sorry Pryce). What’s more, the underlings buy into that line of thinking, too! How fragile must your mental state must be to believe that?

*This isn’t a real thing in the Canon; I’m merely giving a name to a psychological phenomenon wherein the Imperials believe themselves to be better than everyone else and as such don’t believe that their commanders can fail, even given the wealth of evidence to the contrary.

Beyond that, this distancing is very revealing of his character. It says that he values getting the job done over getting the credit (while shrewdly engineering the circumstances so that he gets it anyway). That he values the victory over being seen to be brilliant. To quote Maggie Thatcher: ‘being powerful is like being a lady. If you have to say you are, you really aren’t.’ To apply that to this context: if you have to say you’re brilliant, you really aren’t. Or something like that. To be honest I’m busy picturing Lady Thrawn and oh gods I want that so much.

Serving Another Purpose

I’m saying that phrase a lot today, and I apologise for that. Nevertheless, it does demonstrate the writers’ ability to include so many aspects of character development and story development into just a handful of instances. I’ve talked about the in-universe aspects; it’s time to think of the real-world. The … real world of fictional world story development. Or something. Sorry, I’m still thinking of Lady Thrawn.

Listen to any podcast or read any review (which is fine; you’re perfectly entitled to read whatsoever you wish*), you’ll probably be familiar with the following refrain: ‘You can’t have the bad guy keep losing otherwise they’re not scary!’ usually followed up with ‘But with Thrawn it’s totally okay because losing, to him, is just another source of information’. Bonus points if the review mentions General Grievous from the Clone Wars TV show. Sound familiar? Well, if you don’t listen to any podcasts or read any other reviews** then it wouldn’t, but, well, you’re familiar now! But seriously, I don’t mention these refrains to mock them because I think they’re wrong or anything like that. Indeed, I think they’re generally correct.

*Read: HOW DARE YOU! Your betrayal wounds me deeply and you should feel ashamed.

**You have my undying gratitude for deliberately sticking with my rubbish and not reading something better.

That’s because it’s a constantly difficult and gnawing problem for writers to tackle while trying to manage to have the villain be ever present, to maintain their menace and to keep the show fresh. Enter the incompetent lackeys. On the show, I mean, not in the writer’s room. By having Thrawn send in others to do his bidding to finish the job, it means others are losing to the rebels – which leaves Thrawn relatively spotless and still quite menacing. All that I said about Thrawn maintaining his reputation in my previous point? It isn’t just an in-universe thing but one that can apply to everyone who’s ever said ‘it’s okay for Thrawn to lose because losing, to him, is just another source of information,’ (including me).

This distancing is a great sleight of hand and I’m pleased that they’ve been using it deftly throughout the series. Which I totally picked up on before. Honest.

Setting Up

Did anyone else think it was weird that those Gold squadron pilots were so vehemently against Phoenix squadron’s activities? Shouldn’t they, as rebels, ultimately be for attacking the Empire, no matter how difficult it makes their job? And really it’s rather short-sighted for them to expect the Empire to not take kindly to said attacks. To return to the Peninsular War (I’ll be brief. Promise), the Spanish and Portuguese guerrilleros constantly harassed French soldiers and supply lines. The French response was not good, as you could imagine: for an answer they would wipe out entire villages and also send in more troops, reinforcing their armies and supply lines – thus making the job of the guerrilleros more difficult. But the French response itself had consequences. The more villages they burned, the more villagers they killed, more still would then become guerrilleros to exact a punishment on the French soldiery. The more manpower the French put into protecting supply lines would mean fewer soldiers on the front lines. Then the French would deal out harsher punishments, which in turn bolstered the numbers of the guerrilleros – and on and on until ultimately the French were ejected from Iberia altogether, thanks in large part to those irregular forces. To complete the anecdote, when Wellington invaded France he would mete out harsh punishments … to his own soldiers who assaulted the French citizenry. What’s more, he would pay the locals for any food or damage done by his soldiers. Admittedly he paid with fake coinage, but he insisted that the fake coins have the same amount of gold in them as the real ones. As a result he had absolutely no problem with the French population (or indeed with Boney himself; *mic drop – two centuries too late*). Anyway, don’t kill civilians when you’re invading, is what I’m saying. I’m also saying that, yes, it is making the job much more difficult for other rebel cells, but ultimately it will be worth it.

Whoops. I may have just spoiled Return of the Jedi.

But I happen to think that there was another reason for Gold squadron’s irritation. Well, two actually, and both were acting as set ups. I’m fairly certain that the writers were using the opportunity to set up the main theme of the episode – and I believe so because this is a writing trick that the show uses quite regularly: write in a couple of characters having a fairly inconsequential but adversarial conversation, one that acts as a microcosm of the core premise of the episode – the thing they’re going to explore, on a grander scale, later on. And indeed that’s what we got here: Hera and Mothma had the same conversation, albeit in different terms, about what is better: to continue the fight in the senate or on the front line?

It also acted as a set up to another idea – but one that isn’t even in Rebels: the idea that rebels could even be reticent to fight against the Empire. It sets up [MINOR ROGUE ONE SPOILERS] the rebel council meeting where several members of the rebellion (who were diplomats, if I remember correctly) were ready to flee, to hide from the Empire because they could see no way of taking on the Death Star and winning. In that setting, it was the front line soldiers (again IIRC) who were most willing to take the fight to the Empire, to carry out that suicide mission on Scarif.

Does that sound familiar?

[ROGUE ONE SPOILERS END HERE. YES, MY TWITTER IS A ROGUE ONE SPOILER and I should probably turn off the caps lock now.]

Author: Michael Dare

Michael Dare is a writer, lives in the UK, and has been slowly coming to terms with the realization that he is not Sherlock, but Watson. He loves Star Wars, dislikes blue milk. Enjoys jumping sharks. Survives on the tears of sexist men, and cheeseburgers.